The Fate of the Artist

Collects: OGN

Released: April 2006 (First Second)

Format: 96 pages / color / $17.95 / ISBN: 9781596431331

What is this?: Artist Eddie Campbell details the investigation of his own (fictional) disappearance.

The culprit: Eddie Campbell

I know nothing of artist Eddie Campbell, except that he collaborated with Alan Moore on From Hell. Campbell’s The Fate of the Artist is an “autographical novel” told in many different artistic styles. So many styles, with a thin but baffling plot, that frankly, I don’t know what to make of it.

Fate is nominally about Campbell’s disappearance, narrated by the police officer who investigates. So there’s a lot of interviews with the family, although few of them are straightforward. The daughter is interviewed with crude speech balloons above photos of her. Some of the story is told through comic strips — interactions between Campbell and his wife are in the marital comic “Honeybee,” with other stories told through strips such as “Angry Cook,” “Theatricals,” and “Our Problem Child.” And some of the reminiscences about Campbell are told through straightforward, nine-panel-to-the-page, watercolored comics. When Campbell appears in these, the narration notes Campbell will be played by Richard Siegrist, a fictional actor.

So, first of all: do not expect anything of the plot. Anything. It’s extremely thin, has no real payoff, and is used as a frame for Campbell to talk about what he wants. It’s discarded when it’s convenient. I can’t see why Campbell used his fictional disappearance in an autobiography. He’s obviously talking about things that are very important to him, and the frame only distracts. It’s obviously a metaphor, but a metaphor that doesn’t work in the story is merely a big, distracting sign screaming “Look at me!” into your ear.

So, first of all: do not expect anything of the plot. Anything. It’s extremely thin, has no real payoff, and is used as a frame for Campbell to talk about what he wants. It’s discarded when it’s convenient. I can’t see why Campbell used his fictional disappearance in an autobiography. He’s obviously talking about things that are very important to him, and the frame only distracts. It’s obviously a metaphor, but a metaphor that doesn’t work in the story is merely a big, distracting sign screaming “Look at me!” into your ear.

So, ignore that. Fate is made up of short vignettes, reminiscences of Campbell’s family life, told through his wife, his daughter, and the comic strips. They are melancholy tales, with rarely a happy story among them. Campbell seems obsessed with the ideas of roles — his part is played by Siegrist, the comic strip gives everyone defined comic roles, his observations of the “state of modern marriage.” Campbell’s art tries to break free of those roles in their startling variety, mostly well chosen for their roles. (His daughter in photos is an especially good choice; the comic strip “Honeybee,” which reduces marriage to stereotypical roles and punchlines is another.)

The storytelling is similarly scattershot but isn’t quite as effective. The second part of Fate begins delving into historical characters, real or fictional. Campbell uses this to explore the role viewers play in art: the critics, the audience, contemporaries. He goes from a short essay on reconstructions of lost classical structures to a direct speech on the matter to his own imaginary historical friends, which his daughter calls “a lot of good listeners.” These digressions allow Campbell to make the points he wants to, but it disturbs the book’s narrative (such as it is) and is a bit less artful in saying its piece than the rest of the book.

Which is a shame, because the final section, in which Campbell adapts O. Henry’s “Confessions of a Humorist,” is very well done and much more to the point than anything in the rest of Fate. In the adaptation, in which “the leading role is played by Mr. Eddie Campbell,” Henry and Campbell tell of a humor writer who becomes successful by mining every interaction for nuggets of wit and interest. He becomes despised and unhappy; when he chucks that career to buy into a funeral home, he becomes happy again. The sincerity of “Confessions” bleeds into the pages like the watercolors, and I get the feeling this is more true to Campbell than anything else in Fate, despite it being written about a century ago by another person.

I also have a feeling the people who will like this the most are the ones who have the greatest familiarity with Campbell’s work. Having read none of his work, I was baffled occasionally and disinterested at other times. There is a serious discussion of art and the artist here, but the disconnect between the surface and the symbol are too stark for me to engage with either the discussion or Campbell’s semi-humorous life. (Or this representation of his life.)

Rating: ![]()

![]() (2 of 5)

(2 of 5)

Labels: 2, 2006 April, autobiography, eddie campbell, First Second, ogn

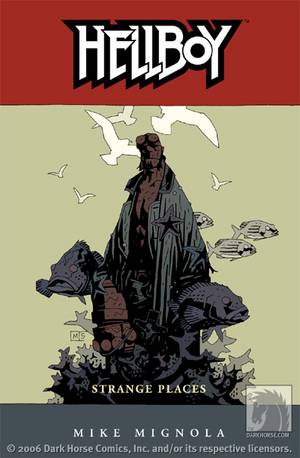

Both “The Third Wish” and “The Island” focus heavily on Hellboy’s destiny. I don’t know if most readers will think thats as boring as I did, but I found it didn’t make for a compelling story. Hellboy seems aimless, tossed from one point on the globe to another, with people yelling at him that he will end the world. Hellboy is baffled, then punches people, and the story ends. It’s less than satisfying. Hellboy doesn’t seem to defy or deny his alleged destiny so much as he reflexively punches those who believe in it.

Both “The Third Wish” and “The Island” focus heavily on Hellboy’s destiny. I don’t know if most readers will think thats as boring as I did, but I found it didn’t make for a compelling story. Hellboy seems aimless, tossed from one point on the globe to another, with people yelling at him that he will end the world. Hellboy is baffled, then punches people, and the story ends. It’s less than satisfying. Hellboy doesn’t seem to defy or deny his alleged destiny so much as he reflexively punches those who believe in it.  (1.5 of 5)

(1.5 of 5)