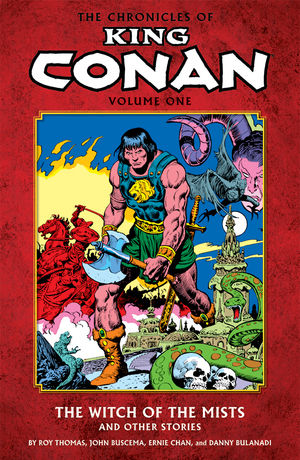

Chronicles of King Conan, v. 1: The Witch of the Mists and Other Stories

Collects: King Conan #1-5 (1980-1)

Released: August 2010 (Dark Horse)

Format: 192 pages / color / $18.99 / ISBN: 9781593074777

What is this?: Conan the barbarian is now the older Conan the king.

The culprits: Writer Roy Thomas and artist John Buscema

As we grow older, we learn things about ourselves. That we have an unexpected talent for cooking, perhaps, or that we’re never going to make it as a major-league shortstop, or if nothing else, that our abilities peak at some point during our youth, and only hard work will keep them from deteriorating in an alarming fashion. It’s a hard lesson to learn but a necessary one as we make the transition from youth to maturity.

In The Chronicles of King Conan, v. 1: The Witch of the Mists and Other Stories, however, writer Roy Thomas informs us that Conan never has to learn that lesson. He will always be at the top of his game, and he never truly reaches that mental maturity. Readers have been following Conan for 80 years — about 50 by the time the issues collected in King Conan came out — and in that time, the barbarian hero has changed little. You might expect that becoming king, with the responsibilities that entails, would change mighty Conan.

You would be wrong. Conan the King is the exact same character as Conan the Barbarian. True, Conan has an army behind him, and he has a son, but it has remarkably little effect on his behavior. And Thomas should know; forty years after Conan the Barbarian #1, v. 1, and Thomas is still the definitive Conan comic book writer.

You would be wrong. Conan the King is the exact same character as Conan the Barbarian. True, Conan has an army behind him, and he has a son, but it has remarkably little effect on his behavior. And Thomas should know; forty years after Conan the Barbarian #1, v. 1, and Thomas is still the definitive Conan comic book writer.

King Conan begins with Conan’s son, Prince Conn, being kidnapped by a Hyperborean witch; King Conan decides to rescue his son alone. Fine; I understand that. But after the rescue and a battle in Zingara, Conan decides to take the fight and his army to Stygia, where Thoth-Amon, the architect of the kidnapping and unrest in Zingara, is hiding. That makes a modicum of sense, although Conan has always shown that a lone hero is better than an army when it comes to defeating wizards and monsters.

But Conan goes himself, and he takes along his heir, Conn. This, of course, is idiotic, as a non-dynastic king like Conan should return home to find his throne occupied and his wife (at best) exiled. Instead, Conan follows Thoth-Amon to the ends of the earth, heading farther and farther from his kingdom, each mile being one more he’ll have to travel on the way back. This is the way of the American action hero, I realize, to take care of such things by himself, but it’s not one of that archetype’s more endearing attributes. There is no cunning to this Conan, and less intelligence. He has no real plan, blundering farther and farther south and endangering his son and his men. I think the idea is that Conan is a pre-historic Alexander, putting the world under his boot, but there’s nothing to support that idea other than Conan’s continuing but illogical success and an inexhaustible supply of willing soldiers.

Conan, as a king, should be confronted with different problems than when he was an adventurer. But there’s no statecraft here or even large-scale battles, no intrigues or imperial entanglements. For some reason, no one engages his army or presents any challenge to them other than their intended adversaries; the countries he invades to fight these wizards don’t protest at all. Why should they? It’s Conan! There are a surfeit of wizards to kill, strange places to visit, usurpers to depose, and monsters to fight — just like before. Such a static world for a character like Conan.

Part of the problem is Thomas’s mania for adapting stories. Issues #1-4 are adapted from stories by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter: “The Witch of the Mists,” “The Black Sphinx of Nebthu,” “Red Moon of Zembabwei,” and “Shadows in the Skull,” which were originally published in the ‘70s and collected in Conan of Aquilonia. Issue #5 starts retelling 1957’s Conan the Avenger, by Björn Nyberg and de Camp, in flashback. It seems odd that Thomas would let other authors choose his opening arc, especially an arc so problematic as those in Conan the Aquilonia. That’s not to say Thomas slavishly followed the original stories or that adapting stories is a bad idea; for instance, Thomas’s creation of Red Sonja was a result of adapting a non-Conan story by Robert E. Howard, “The Shadow of the Vulture.” And I understand that those four stories had the setup that Thomas wanted to start with. But I think using those stories at a later point would have been a better idea.

There are two redeeming points to King Conan. One is the book shows the maturation of Conn. His father is an impossible role model to live up to, but he tries anyway. He kills his first man in this book, and he gets a glimpse of true evil in Thoth-Amon. If Conan had sent Conn on a military campaign while Conan stayed at home, to get the boy some seasoning, this might have been a fascinating story, although it would have made it into Conan: The Next Generation. (Not that I would have minded.) The idea of telling the story of this prince maturing into a man is a good one; it’s just not what the book is about.

The second highlight is John Buscema’s art. Thomas is Conan’s definitive writer, and Buscema is one of the two most celebrated Conan artists. His Conan is much the same as it was in Conan the Barbarian — he has crow’s feet, and his hair is grayer, but he’s still strong as ever. His Conn is more realistic, strong for a teenager but obviously not Conan. Since the material is much the same as Conan the Barbarian, he gets to draw monsters and wizards and … well, not many scantily clad women, but there are some. Fans of Buscema’s Conan work will likely not be disappointed.

But they won’t be surprised, either. And that’s the problem with King Conan. Despite the change in premise, there is little to discover that you can’t find in Dark Horse’s Chronicles of Conan series.

Rating: ![]()

![]() (1.5 of 5)

(1.5 of 5)

Labels: 1.5, 2010 August, Conan, Conn, Dark Horse, John Buscema, King Conan, Marvel, Roy Thomas

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home