Last year, I finished reading

The Complete Ben Reilly Epic, Book 6, which meant I had read, from beginning to end, all three of the Unholy Trinity of Bad Marvel ‘90s Crossovers:

• The Clone Saga

• Onslaught

• The Crossing

All three are terrible, terrible stories, produced at about the same time: around 1995 and 1996. That is, all three were churned out after the speculator boom of the early ‘90s and just as Marvel was heading into bankruptcy. (In fact, the Clone Saga ended with issues cover dated December 1996, the month Marvel filed for Chapter 11 protection.)

All three of these crossovers are terrible. Whether they were commercially driven abominations or horrendously misguided attempts to overhaul a line, or both, each had confused storylines and a deleterious effect on a line.

Which, though, was the worst? This is a question that people will argue about; I have a feeling most fans’ answers would depend on which abused character they like the most. Still, I think some characters received a considerably shorter end of the stick than the others. (The Fantastic Four avoided the worst of this, although it should be noted that

Atlantis Rising won’t be confused for Shakespeare any time soon.)

Onslaught

Onslaught is the least offensive of these mega-crossovers. For those of you who don’t know, Onslaught was a psionic entity created in Professor Xavier’s mind after he wiped Magneto’s mind. After ominous foreshadowing and the resolution of the long-dangling X-Traitor plot, Onslaught burst forth, took over New York with the help of Sentinels, and … didn’t do much. There was muttering of conquest, but it didn’t go anywhere.

Length: Relatively short. The actual crossover itself is contained in four trade paperbacks, and one of those doesn’t even have any X-Men titles in it. However, if you throw in the lead-up to the actual crossover, you have to include another three trades. The lead up and crossover ate up about fifteen months; the crossover itself blew over in a summer.

Spillover: The actual crossover (and some of its foreshadowing) pulled in quite a few titles, including the Clone Saga (see below).

Incredible Hulk,

Avengers,

Fantastic Four,

Iron Man, and

Thor all got caught up in the crossover, which is a shame, given that all those series (except

Hulk ended when Onslaught did.

Creepy dude moment: When Jean Grey explored Professor Xavier’s thoughts in

X-Men #53 and discovered a repressed memory (a flashback to

Uncanny X-Men #3) that Xavier had a crush on Jean from the beginning. Not standing so close to him isn’t going to help when he can telepathically crush on her wherever she is.

Damage: To the X-characters, not much. Professor Xavier was shuffled off the page — you know, because of his crimes against humanity and whatnot. The character itself wasn’t damaged too much as what Onslaught did can be considered separate from Xavier. Mutants were hated even more, although that’s par for the course.

The rest of the Marvel Universe was remade by Onslaught (at least for a year). The

Avengers and its subsidiary titles were all canceled, as was

Fantastic Four; Mark Waid and Ron Garney’s well-received

Captain America run was axed in favor of a commercial stunt.

FF,

Iron Man,

Avengers, and

Captain America were all leased to Image creators for a year. Rob Liefeld’s Extreme Studios got the latter two, while Jim Lee’s Wildstorm got

FF and

Iron Man. The titles were rebooted, with almost 35 years of continuity being tossed out for a year. Also: Liefeld drew the weirdest Captain America.

Mitigation: Sales rose on those old titles; all of them, except perhaps

Captain America, needed the added attention and sales. More importantly, Onslaught wiped out the damage The Crossing caused, and that’s almost a blessing.

The Clone Saga

Now we’re getting into the heavy hitters. In the Clone Saga — a sequel to a ‘70s story that had to be confusingly retitled

The Original Clone Saga — a clone of Peter Parker returns to New York to confront Peter. The clone, who calls himself Ben Reilly, is followed by Kaine, another clone who hates Ben, and the Jackal, who created those two clones plus others … Ben and Peter argue about who’s the clone, Peter steps down as Spider-Man when he loses his powers and has a baby on the way, and then a figure from the past comes to take credit for everything that’s happened in Peter’s life.

Length: Interminable. The crossover ate up two years of the four Spider-titles plus ancillary titles like

Spider-Man Unlimited and

Spider-Man Team-Up. More than 100 issues were thrown at this story! The creators backtracked, laid false trails, changed their minds (OK, so it was mostly editors and the business people who changed their minds), and generally squandered months and months of Spider-Man stories. The fruit of their labors filled eleven trade paperbacks.

It’s hard to get across how much ink and paper was wasted on the Clone Saga. Spider-Man has always been a character who can support the one-issue story, but combined with many throwaway stories were the idiocy of the Jackal and Spidercide, Gaunt and Seward Trainer, Scrier and Judas Traveler and hosts of other villains who had no purpose other than to look mysterious and prevent any resolution to the story.

And when they went to wrap it up, all it took was a four-issue story. Just one month! Why couldn’t they have done that a year earlier?

Spillover: Relatively little. Spider-Man’s troubles didn’t affect other titles much. The clone, going by the alias of Scarlet Spider, kinda joined the New Warriors, and he appeared as Spider-Man in an issue of

Daredevil. The Clone Saga also brushed up against the status quos of Punisher, Green Goblin, and Venom, but no one cared about the Phil Urich Green Goblin at the time, and the Punisher and Venom series are both best forgotten. I mean, the Punisher had a ponytail, and no one wants to acknowledge that.

Really, despite the crossover allegedly being so popular, no one else wanted to touch it.

Creepy dude moment: When Peter smacked his wife. It was portrayed as an accident, Peter lashing out randomly after learning he was a clone, but it happened. One moment of frustration and insanity labeled Ant-Man a wifebeater forever, but the same standard wasn’t applied to Peter hitting Mary Jane. This is for two reasons: a) The storyline in which Ant-Man hit the Wasp was good and not best forgotten, like the Clone Saga, and b) People actually like Spider-Man.

Later, Peter tried to kill Mary Jane, but he was being mind controlled, which is understandable and normal behavior for superheroes.

Damage: After two years, the creators realized how badly the entire idea was, and they tried to put everything back where it was while providing a satisfying conclusion. What they did satisfied few, except in the sense that it allowed everyone to put the clone nonsense behind them and forget about it.

The Clone Saga, in its blind grasping for sense and sensation, committed several sins that should be unforgivable. It brought Norman Osborn back from the dead as the architect of the Clone Saga. It killed Ben despite his potential because he was a loose end and a reminder of the Clone Saga’s sins. It caused Mary Jane and Peter’s daughter to be stillborn, then held out hope that the child was merely kidnapped. It made Peter do bad things to Mary Jane.

It made Peter Parker into a clone for a while, which was stupid. It told us, “Everything you know is wrong.” Everything we knew was published by Marvel Comics, which should have been a tipoff that Marvel’s output was not the most reliable source.

Mitigation: The crossover had many ideas that were worth exploring. Peter having a child and moving on isn’t a bad idea, but there’s no reason he had to be labeled the clone for the idea to work. Kaine wasn’t interesting at the time, but he has been used well in the last few years. Getting rid of Aunt May was long overdue; it allowed Peter to grow some. I even have some sympathy for using Kaine to get rid of some of Spider-Man’s older adversaries, although the new Doctor Octopus didn’t pan out.

Most impressive is Ben Reilly. Seeing a different Peter, one who had been lost for years and coming back to a different Peter who had grown but had also gotten a bit lost, presented the reader with an interesting contrast. (Ben wouldn’t have cut a deal to allow for uneasy coexistence with Venom, but he also might not have given Sandman a chance to reform.) Ben’s existence was wasted, of course — except in the M2 Universe, which picked up on some of these threads in

Spider-Girl.

Avengers: The Crossing

Iron Man kills a few women to hide a secret: he’s been working with Kang for years to help Kang, Mantis, and their Chrononauts invade Earth and conquer it using his time-travel powers. Kang does manage to erase Vietnam from almost everyone’s memories, but that’s about as far as his conquest goes.

Length: A little longer than the core Onslaught crossover but much shorter than Onslaught’s foreshadowing. The Crossing took place over half a year, and its contents — a mere 25 issues — were reprinted in a single oversized omnibus. (You can pick up the omnibus for about

$30 on Amazon, although two insane people gave the book three-star reviews. Three stars! Why not give the book a whole constellation?)

Spillover: None, as far as I can see. The number of titles involved was admirably restrained: only

Avengers,

Force Works (formerly

Avengers West Coast),

Iron Man, and

War Machine were involved in the story. Thor and Captain America stayed the hell away from The Crossing, which shows excellent sense.

Creepy dude moment: Everything Iron Man does in this book. In addition to killing three unarmed women (and no men), he blasts Wasp so hard the measures taken to save her life turn her into a wasp-human hybrid. (She seemed fine with that, though.) He kidnaps a couple of other women close to him. I suppose you could make a case that this is the flipside to the charmingly predatory nature of Tony’s normal persona — he uses and seduces women — but this turn has the subtlety of an atom bomb lobbed through a store window.

Damage: Holy God, did this do a number on Iron Man. Iron Man had been corrupted by Kang and was working for him for pretty much the entire Marvel Age of Heroes, although the story gives him no motivation to do so. To protect his secret, Tony declared war on women. And this is the guy upon the Marvel Cinematic Universe was built about a decade later!

Because a series starring a traitorous murderer would have been a problem, Marvel killed off old Tony and replaced him with a teenage version from a different timeline. Teen Tony couldn’t be too different, though, so the fight that introduces him to the main Marvel Universe ends with him suffering heart damage.

The art is inconsistent and usually awful. Instead of giving the secondary titles a sales boost, The Crossing failed

War Machine and

Force Works so thoroughly they were cancelled two months later. Obscure, best-forgotten continuity is crucial to the story, and readers are expected to remember things like who Yellowjacket II and Gilgamesh are. The story has tons of forgotten and unimportant characters wandering through it; sometimes we’re even supposed to care about them. (The death of Gilgamesh is supposed to be momentous, and the story can’t get that across.) Mantis wanting revenge on the Avengers makes no sense, and Kurt Busiek retconned her (and most of Kang’s soldiers) into Space Phantoms in

Avengers Forever. Adult versions of Luna (Quicksilver and Crystal’s daughter) and the Vision and Scarlet Witch’s kids run rampant throughout the story, working for Kang, and no one can figure out who they are. War Machine has a horrifically ugly suit of armor. (I wonder what happened to it …?)

Mitigation: Onslaught / Heroes Reborn and Avengers Forever cleaned up so much of the mess from this crossover that we don’t

have to remember it any more. Otherwise, this book had no redeeming features.

Verdict

The Crossing is the worst of these; it’s so bad, the omnibus should be marked as hazardous waste. Still, it doesn’t have much of an effect on modern Marvel continuity. The Clone Saga gave us the returned Green Goblin and Kaine; Onslaught briefly ended decades of continuity in tangentially related titles and really launched the “Professor Xavier is a monster” idea into the wild. Again: The Crossing was published in 1995.

Iron Man came out in 2008. In 13 years, the worst storyline in Marvel history was wiped from the timeline as thoroughly as Kang wanted to wipe out the resistance to him.

Labels: Avengers, Clone Saga, Crossing, Marvel, Onslaught, Spider-Man, X-Men

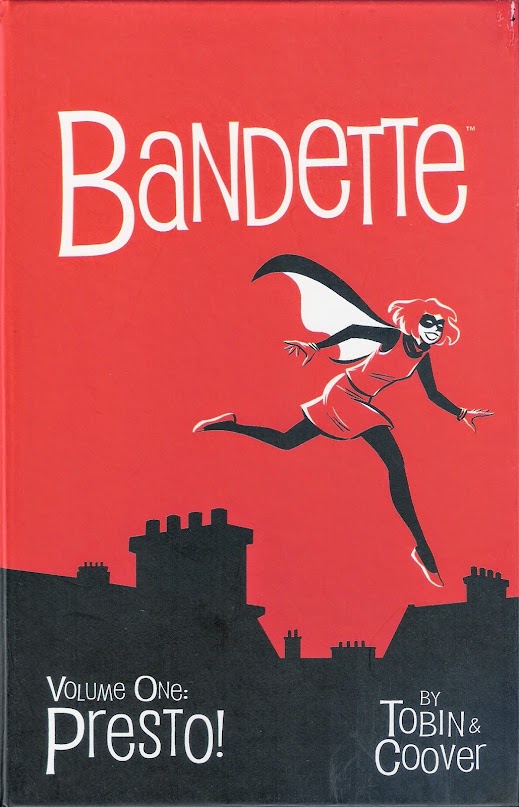

At this stage in the review, you’ll know if this book is for you. Many people will have already written off Bandette as sickly sweet. That is not the case, though. Coover and writer Paul Tobin skirt that pitfall as deftly as is possible, keeping Bandette carefree and lighthearted without being cloying; the protagonist is confident and sure of her abilities in a way that allows her to remain unconcerned yet exhilarated in the face of assassins and bank robbers.

At this stage in the review, you’ll know if this book is for you. Many people will have already written off Bandette as sickly sweet. That is not the case, though. Coover and writer Paul Tobin skirt that pitfall as deftly as is possible, keeping Bandette carefree and lighthearted without being cloying; the protagonist is confident and sure of her abilities in a way that allows her to remain unconcerned yet exhilarated in the face of assassins and bank robbers.