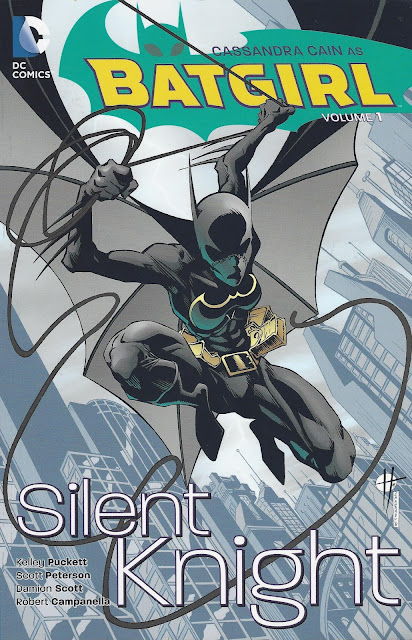

Batgirl, v. 1: Silent Knight

Collects: Batgirl #1-12, Annual #1 (2000-1)

Released: January 2016 (DC)

Format: 328 pages / color / $19.99 / ISBN: 9780785199571

What is this?: Coming out of No Man’s Land, a new Batgirl, able to predict the movement of others, joins Batman’s fight against crime.

The culprits: Writers Kelley Puckett and Scott Peterson and artist Damion Scott (and others)

My interest in the Batman titles waxes and wanes, but I rarely read the second-tier Bat books. For some reason, I made an exception with Batgirl, v. 1: Silent Night, and I’m glad I did.

The Batgirl in this book is Cassandra Cain, a character who debuted in 1999’s No Man’s Land event. Cassandra is the daughter of assassin David Cain, who trained her to fight from nearly birth but neglected language of any kind; as a consequence, the language centers of Cassandra’s brain were entirely dedicated to interpreting body language, which allows her to foresee her opponents’ moves but leaves her with little language ability.

In Silent Knight, Batgirl doesn’t have a ready-made archenemy, nor does she acquire one. She beats up on Gotham’s mooks and killers, usually experiencing little trouble. She’s not perfect, however; sometimes, she is injured while fighting crime, and sometimes people she wants to save die.

In Silent Knight, Batgirl doesn’t have a ready-made archenemy, nor does she acquire one. She beats up on Gotham’s mooks and killers, usually experiencing little trouble. She’s not perfect, however; sometimes, she is injured while fighting crime, and sometimes people she wants to save die.The lack of an overarching story is for the best, really, as it allows the story to concentrate on Cassandra herself, who is more interesting than a recurring supervillains. The book’s plot is driven by Cassandra’s personal evolution, with Cassandra having to fit into the Bat-family while she changes as a person. Her identity is wrapped up in her fighting ability, and anything that threatens her greatness at that has to be overcome at any cost. She has lived a life insulated from so many things that normal people take for granted; her only real human contact has been the father who expressed his feelings for her through violence. Because of this, she responds to male authority figures, obeying Batman’s commands and even showing concern for him.

The Batman / Batgirl relationship is touching in its way, but it’s also disturbing, given Cassandra’s relationship with her father. Cassandra rejected Cain long before the series, just after he sent her on her first assassination, but she still has feelings for the man who forced her to become a fighting machine. Batman is absurdly concerned that Cassandra might have killed a man when she was a little girl — she wasn’t legally or morally culpable, and she’s certainly repented — and as her surrogate father, he beats the tar out of her biological father because Cain “made her like us.”

(I have to admit: I like Cain, even though he’s despicable. He taunts Batman over his inability to accept Cassandra’s origins, and even hobbled by injuries, he’s resourceful and hard to defeat. His lingering affection over Cassandra — or what he created — is a nice Achilles heel for him as well.)

Cassandra lives with Oracle (Barbara Gordon), the first Batgirl, but despite sharing living space and a codename, Cassandra doesn’t show Barbara the sort of tenderness she does Batman. I’m not sure why this is. The generation gap isn't to blame, since Cassandra doesn’t interact with anyone her age. Is Cassandra rejecting the emotions Barbara exudes when she offers Cassandra help? Or does Barbara’s paralysis distance and reliance on communication her from someone who defines herself by motion? I think it has more to do with the latter than the former, but it’s hard to say.

Silent Knight is a great value: thirteen issues, one of them an annual, for $20. DC has always been better at getting older series like Batgirl reprinted for a reasonable price, but that has sometimes come at the cost of the quality of the physical book. Silent Knight has a higher quality paper and better binding than previous DC offerings, like the reprint of Chase from four years ago. A Marvel trade of this size … well, because I like picking on it, Cage: Second Chances, v. 1 is eight pages shorter and costs $15 more. Also: It’s filled with reprints of issues of Cage, so Silent Knight could have been 300 blank pages and still come out ahead.

On the other hand, the book does have some dead space. The issue that’s part of the Officer Down crossover (#11) feels like it’s acknowledging the event while giving Cassandra something to do with no real consequences; because it doesn’t engage with Barbara’s connection to Commissioner Gordon other than to mention it, the issue seems like a waste. The annual at the end of Silent Knight is filler — Batman and Batgirl in India — although it does show Cassandra watching a movie for the first time.

I’m not overly thrilled about the appearance of Lady Shiva either, but that’s mostly because she and Cassandra are hinted to have a connection because their skin colors are near each other on the color wheel and they have a similar ability. I’m not sure what my feelings will be as their connection is explored, though.

Damion Scott’s art is very, very ‘90s, even though these issues were coming out at the beginning of the 2000s. Scott’s work is sometimes described as being influenced by hip-hop and graffiti, which is fair, but comics readers who remember the ‘90s will see similarities to Joe Madureira’s work, full of thick lines and jutting angles. Scott is from the school of thought that a character’s mask should represent their emotions, so Batgirl’s (and Batman’s) mask have widened eyes, and the sewed-shut mouth of Batgirl’s costume widens and twists as necessary. (That sewed-shut mouth is delightfully creepy, I have to say.) I can’t say I am fond of Scott’s style, but it took no time before I became accustomed to it as the style of Batgirl, just as a quirky authorial voice often becomes part of the background — or even beloved — after you’ve been exposed to it long enough.

What never becomes part of the background is the way Batgirl is sexualized. When drawn in street clothes, Cassandra is a teenage girl of normal proportions, or as close as a comic-book female generally gets. As Batgirl … Batgirl is absurdly busty, and I can’t think of a reason why. Nothing about Cassandra in either persona justifies such objectification, and Scott’s depiction of Cassandra shows he understands normal female proportions. Is it a problem with the prominence of the costume’s logo? I dunno. Whatever the reason, it’s distracting.

Silent Knight is a solid superhero book that doesn’t rely on stunts or cheap traumas to shock readers. It develops a character with an interesting hook by putting her into situations readers are familiar with and seeing what happens. I liked this book so much, in fact, that I’m disappointed now that I didn’t preorder the second volume, To the Death. Guess I’ll have to pick it up after it comes out.

Rating:

Labels: 2016 January, 4, Batgirl II, Cassandra Cain, Damion Scott, David Cain, Gotham City, India, Kelley Puckett, Scott Peterson

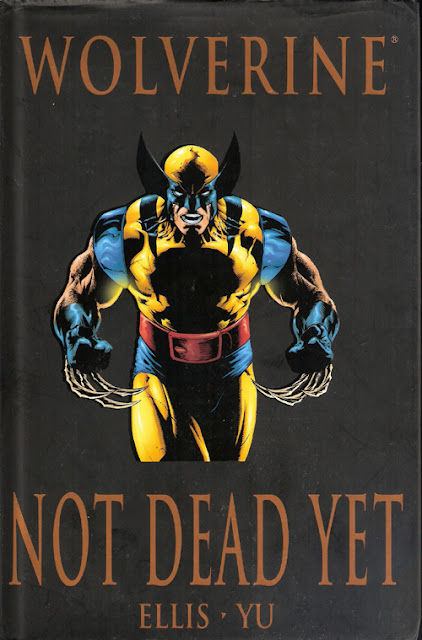

Stage Three: The Old Man, represented by

Stage Three: The Old Man, represented by  After discovering who he is, it is time for man to be the best he that he can be at what he does, even if it isn’t pretty. If that means composing symphonies and choral works, so be it. If your burden is that you have an outstanding mechanical aptitude, it’s up to you to embrace, not shirk, that destiny. If, like Wolverine, killing a lot of people is what you do, then you need to do it, and do it as often as possible.

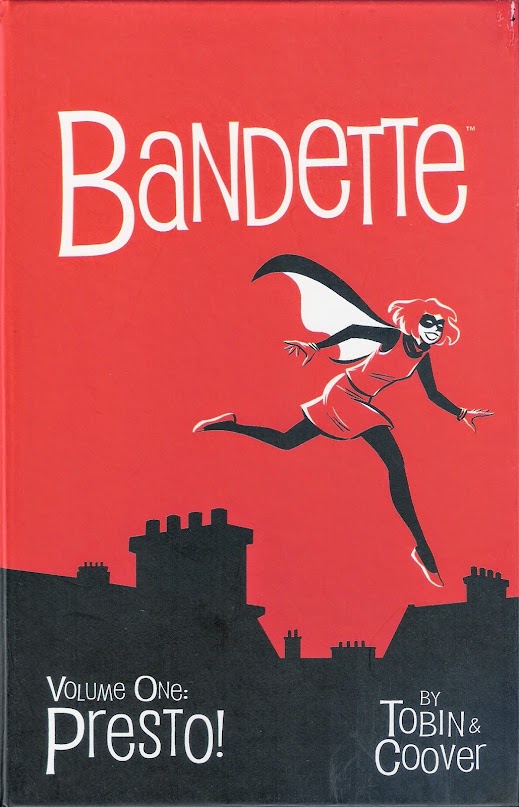

After discovering who he is, it is time for man to be the best he that he can be at what he does, even if it isn’t pretty. If that means composing symphonies and choral works, so be it. If your burden is that you have an outstanding mechanical aptitude, it’s up to you to embrace, not shirk, that destiny. If, like Wolverine, killing a lot of people is what you do, then you need to do it, and do it as often as possible.  Stage One: The Enigma, represented by

Stage One: The Enigma, represented by